2015 - 17 - Curator, The Moving Image Project

Artists: Yu Araki, Jaime Castro, Elly Clarke, Eleanor Cunningham, Camille de Saint-Jean, Karl England, Nicolas Feldmeyer, Craig Green, Jaime Humphreys, Hui-Hsuan Hsu, Will Kendrick, Laura Leahy, Joe Newlin, Miranda Parkes, Chinmoyi Patel, Nathan Pohio, Frazer Price, James Quin, Antonio Roberts, Daniel Salisbury, Patrick Segura, Vishwa Shroff, John Stewardson, Wood and Harrison

Tokyo, JPN, Baroda, IN, Christchurch, NZ, Bushwick, NY, London, UK

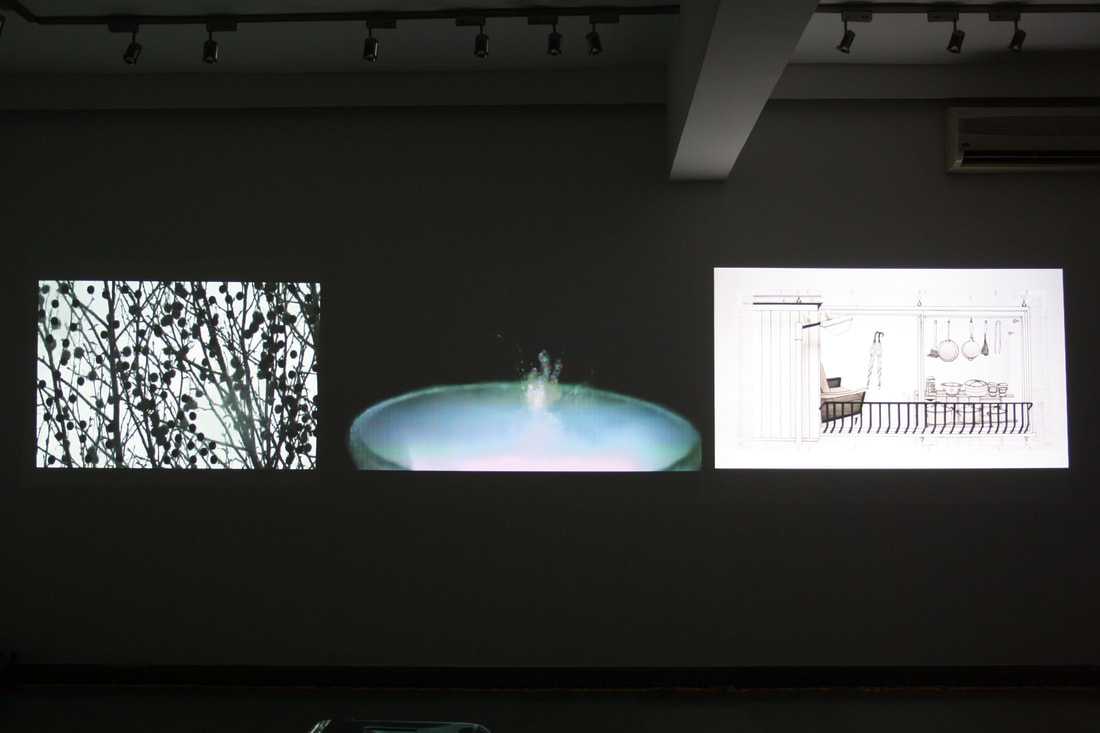

In the vein of a travelling circus, The Moving Image Project is made up of a curious mix of images and films that are going on a journey. UK curator Charlie Levine has invited various artists from around the world to submit short silent films or still images that she will show via her mobile phone and pico projector wherever she goes. As ringmaster she will pick and chose location and artwork along the way, as well as pick up new participating artists, advertising its presence via an online notice board. The Moving Image Project is about encounter, transience, travel and catching a glimpse. It encourages conversation, interaction and mimics Duchamp’s Museum in Suitcase, the idea that you can travel the world with an exhibition, in this case, in the palm of your hand.

The Moving Image Project text by James Quin, Sept 2014

Charlie Levine’s The Moving Image Project brings together a collection of artists short films, each with duration no longer than eight minutes with some films so short that they barely register as anything more than a split second caught in the corner of the eye whilst travelling on a high speed train. Levine’s platform of choice is a mobile phone connected to a pico projector, a choice of technology that has allowed her to show the corpus of work in galleries, coffee shops, airplanes and even on that most intimate of ‘screens’ – the body - in this case, palms of the hand. The project to date has been seen in London, Tokyo, New York and points in-between.

Anyone familiar with long distance air travel experiences an expansion and contraction of time combined with spatial indeterminacy, a liminal world of ‘in-between-ness’, neither here nor there, past or future, an extended present-ness that encapsulates the boredom of the long haul flight and accompanying succession of transitory worlds apprehended at a glimpse. Levine is a curator ‘on the move’, and it is this crossing of geographical boundaries and more importantly the deterritorialisation of time-zones that seems to have been the impetus for The Moving Image Project. Levine’s The Moving Image Project literally becomes one of ‘images on the move’.

The emergence of technologies such as the railway and the telegraph in the 1870’s formed the world in which we now live, specifically the way in which we, as temporal beings ‘think’ time. Rebecca Solnit in her excellent book Motion Studies: Time, Space and Eadweard Muybridge makes the case that the ‘annihilation of time and space’ through such technologies was inseparable from the development of the ‘moving picture’. What agency might the mobile phone possess in reconfiguring our relation to time in the present? Hungarian philosopher Kristóf Nyíri in Time and the Mobile Order argues that “[t]he mobile phone, rather than breaking up time, gives rise to a new synthesis of mechanical time and organic time”.

Levine’s project may shed light on this synthesis of mechanical and organic time in the mobile phone’s enabling of “recurrent programme reshuffling - communication that coordinates movement in space and time while” ‘on the move’, let alone its ancillary, though handy ability to store and project images.

Film and photography has an especially privileged relation to time, continuing to fascinate the temporal (human) being in its ability to reanimate the inanimate and its concomitant capacity to conflate temporal registers – the then, next, after, past, present and future that are inextricably bound to the medium. In Levine’s The Moving Image Project these registers are further complicated by her decision to edit together disparate short films in a time line and loop them for the duration of their showing.

It is this process of looping, return and therefore a deferred closure that uncovers films ability to unravel the linear time-line and ultimately challenge conventional narrative in film as thematised in Gilles Deleuze’s ‘Movement-Image’ in contradistinction to what he described as the ‘Time-Image’. In Levine’s The Moving Image Project what we essentially encounter is a Deleuzian ‘Time-Image’ or ‘Crystal Image of Time’, where the montaged short films function as a hall of mirrors, infused with past, present and future. The reshuffling of sequence or a re-ordering of the films time-line allows another facet of the ‘Crystal-Image of Time’ to become apparent - through ‘difference’.

There is another layer to Levine’s project that is worth noting here, and it is a layer in absentia – one of sound. Due to necessity, the films are shown without accompanying soundtrack or dialogue; they are resolutely silent, rendering them a dream-like quality. It is this silence that inadvertently connects Levine’s project to an earlier ‘silent’ incarnation of cinema - the cinema of Dziga Vertov. Some of the short film pieces chosen by Levine interrogate relations between the still and moving image within film, and, perhaps the most powerful and insightful example of this relation can be found in Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), where the moving image of a white horse at full trot is cut to a still image of the horse. The affect is breathtaking, a stillness that seems to expose, according to numerous film theorists, ‘cinemas secret subject’, that of stillness.

In conversation with Levine I was interested to hear The Moving Image Project, described as a “show reel”. Again, this seems to expose anachronistic (in this sense –‘up against time’- rather than the pejorative ‘out of fashion’) comparisons with emergent 19th century cinematic technologies and the forums for their dissemination. “Show reel”, puts us in mind of earlier manifestations of the moving image, the zoetrope, Praxinoscope, Cinématographe and the Magic Lantern where the operative word would be “show” and, the not yet realised ‘reel’, and more importantly, in the context of Levine’s project, the venues in which such proto-cinematic technologies were to be encountered,

Levine’s projections of The Moving Image Project into coffee shops, galleries, the interiors of aircraft fuselages and the extremities of the human body, are part of a long tradition of ‘the spectacle and spectacular’, the shared encounter of the strange and the uncanny, the tented travelling circus of curiosities and world fairs. And yet an equally prevalent 19th century preoccupation was in communication with an altogether different world - the world of séance and spirit, the attempt to reanimate the inanimate. What, if nothing else is film and photography, if it is not a form of haunting, and, are we not engaged as both spectators and creators of images in a perpetual conversation with the dead?

It would be worthwhile to conclude my own thoughts on Levine’s fascinating The Moving Image Project by placing it alongside, ‘Duchamp’s Box in a Suitcase’ and Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, as examples of proto-sampling. What might they have in common? The answer is very much. At the risk of oversimplification, all three projects, rooted, as they are in their respective ‘present and pasts’, have an ‘eye on the future’ and I wait with interest to see how this project develops as Levine continues her The Moving Image Project, on the move.

Anyone familiar with long distance air travel experiences an expansion and contraction of time combined with spatial indeterminacy, a liminal world of ‘in-between-ness’, neither here nor there, past or future, an extended present-ness that encapsulates the boredom of the long haul flight and accompanying succession of transitory worlds apprehended at a glimpse. Levine is a curator ‘on the move’, and it is this crossing of geographical boundaries and more importantly the deterritorialisation of time-zones that seems to have been the impetus for The Moving Image Project. Levine’s The Moving Image Project literally becomes one of ‘images on the move’.

The emergence of technologies such as the railway and the telegraph in the 1870’s formed the world in which we now live, specifically the way in which we, as temporal beings ‘think’ time. Rebecca Solnit in her excellent book Motion Studies: Time, Space and Eadweard Muybridge makes the case that the ‘annihilation of time and space’ through such technologies was inseparable from the development of the ‘moving picture’. What agency might the mobile phone possess in reconfiguring our relation to time in the present? Hungarian philosopher Kristóf Nyíri in Time and the Mobile Order argues that “[t]he mobile phone, rather than breaking up time, gives rise to a new synthesis of mechanical time and organic time”.

Levine’s project may shed light on this synthesis of mechanical and organic time in the mobile phone’s enabling of “recurrent programme reshuffling - communication that coordinates movement in space and time while” ‘on the move’, let alone its ancillary, though handy ability to store and project images.

Film and photography has an especially privileged relation to time, continuing to fascinate the temporal (human) being in its ability to reanimate the inanimate and its concomitant capacity to conflate temporal registers – the then, next, after, past, present and future that are inextricably bound to the medium. In Levine’s The Moving Image Project these registers are further complicated by her decision to edit together disparate short films in a time line and loop them for the duration of their showing.

It is this process of looping, return and therefore a deferred closure that uncovers films ability to unravel the linear time-line and ultimately challenge conventional narrative in film as thematised in Gilles Deleuze’s ‘Movement-Image’ in contradistinction to what he described as the ‘Time-Image’. In Levine’s The Moving Image Project what we essentially encounter is a Deleuzian ‘Time-Image’ or ‘Crystal Image of Time’, where the montaged short films function as a hall of mirrors, infused with past, present and future. The reshuffling of sequence or a re-ordering of the films time-line allows another facet of the ‘Crystal-Image of Time’ to become apparent - through ‘difference’.

There is another layer to Levine’s project that is worth noting here, and it is a layer in absentia – one of sound. Due to necessity, the films are shown without accompanying soundtrack or dialogue; they are resolutely silent, rendering them a dream-like quality. It is this silence that inadvertently connects Levine’s project to an earlier ‘silent’ incarnation of cinema - the cinema of Dziga Vertov. Some of the short film pieces chosen by Levine interrogate relations between the still and moving image within film, and, perhaps the most powerful and insightful example of this relation can be found in Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), where the moving image of a white horse at full trot is cut to a still image of the horse. The affect is breathtaking, a stillness that seems to expose, according to numerous film theorists, ‘cinemas secret subject’, that of stillness.

In conversation with Levine I was interested to hear The Moving Image Project, described as a “show reel”. Again, this seems to expose anachronistic (in this sense –‘up against time’- rather than the pejorative ‘out of fashion’) comparisons with emergent 19th century cinematic technologies and the forums for their dissemination. “Show reel”, puts us in mind of earlier manifestations of the moving image, the zoetrope, Praxinoscope, Cinématographe and the Magic Lantern where the operative word would be “show” and, the not yet realised ‘reel’, and more importantly, in the context of Levine’s project, the venues in which such proto-cinematic technologies were to be encountered,

Levine’s projections of The Moving Image Project into coffee shops, galleries, the interiors of aircraft fuselages and the extremities of the human body, are part of a long tradition of ‘the spectacle and spectacular’, the shared encounter of the strange and the uncanny, the tented travelling circus of curiosities and world fairs. And yet an equally prevalent 19th century preoccupation was in communication with an altogether different world - the world of séance and spirit, the attempt to reanimate the inanimate. What, if nothing else is film and photography, if it is not a form of haunting, and, are we not engaged as both spectators and creators of images in a perpetual conversation with the dead?

It would be worthwhile to conclude my own thoughts on Levine’s fascinating The Moving Image Project by placing it alongside, ‘Duchamp’s Box in a Suitcase’ and Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, as examples of proto-sampling. What might they have in common? The answer is very much. At the risk of oversimplification, all three projects, rooted, as they are in their respective ‘present and pasts’, have an ‘eye on the future’ and I wait with interest to see how this project develops as Levine continues her The Moving Image Project, on the move.